Leadership and Organizational Behavior

Organizational Behavior (OB) is the study and application of knowledge about how people, individuals, and groups act in organizations. It does this by taking asystem approach. That is, it interprets people-organization relationships in terms of the whole person, whole group, whole organization, and whole social system. Its purpose is to build better relationships by achieving human objectives, organizational objectives, and social objectives.

As you can see from the definition above, organizational behavior encompasses a wide range of topics, such as human behavior, change, leadership, teams, etc. Since many of these topics are covered elsewhere in the leadership guide, this paper will focus on a few parts of OB: elements, models, social systems, OD, work life, action learning, and change.

Elements of Organizational Behavior

The organization's base rests on management's philosophy, values, vision and goals. This in turn drives the organizational culture which is composed of the formal organization, informal organization, and the social environment. The culture determines the type of leadership, communication, and group dynamics within the organization. The workers perceive this as the quality of work life which directs their degree of motivation. The final outcome are performance, individual satisfaction, and personal growth and development. All these elements combine to build the model or framework that the organization operates from.

Models of Organizational Behavior

There are four major models or frameworks that organizations operate out of, Autocratic, Custodial, Supportive, and Collegial (Cunningham, Eberle, 1990; Davis ,1967):

- Autocratic — The basis of this model is power with a managerial orientation of authority. The employees in turn are oriented towards obedience and dependence on the boss. The employee need that is met is subsistence. The performance result is minimal.

- Custodial — The basis of this model is economic resources with a managerial orientation of money. The employees in turn are oriented towards security and benefits and dependence on the organization. The employee need that is met is security. The performance result is passive cooperation.

- Supportive — The basis of this model is leadership with a managerial orientation of support. The employees in turn are oriented towards job performance and participation. The employee need that is met is status and recognition. The performance result is awakened drives.

- Collegial — The basis of this model is partnership with a managerial orientation of teamwork. The employees in turn are oriented towards responsible behavior and self-discipline. The employee need that is met is self-actualization. The performance result is moderate enthusiasm.

Although there are four separate models, almost no organization operates exclusively in one. There will usually be a predominate one, with one or more areas over-lapping in the other models.

The first model, autocratic, has its roots in the industrial revolution. The managers of this type of organization operate mostly out of McGregor's Theory X. The next three models begin to build on McGregor's Theory Y. They have each evolved over a period of time and there is no one best model. In addition, the collegial model should not be thought as the last or best model, but the beginning of a new model or paradigm.

ocial Systems, Culture, and Individualization

A social system is a complex set of human relationships interacting in many ways. Within an organization, the social system includes all the people in it and their relationships to each other and to the outside world. The behavior of one member can have an impact, either directly or indirectly, on the behavior of others. Also, the social system does not have boundaries... it exchanges goods, ideas, culture, etc. with the environment around it.

Culture is the conventional behavior of a society that encompasses beliefs, customs, knowledge, and practices. It influences human behavior, even though it seldom enters into their conscious thought. People depend on culture as it gives them stability, security, understanding, and the ability to respond to a given situation. This is why people fear change. They fear the system will become unstable, their security will be lost, they will not understand the new process, and they will not know how to respond to the new situations.

Individualization is when employees successfully exert influence on the social system by challenging the culture.

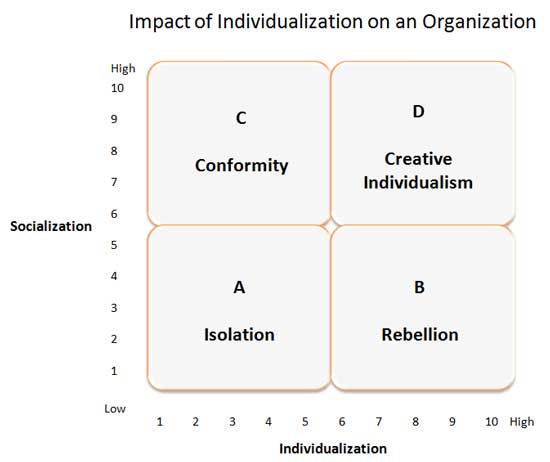

The quadrant shown below shows how individualization affects different organizations (Schein, 1968):

- Quadrant A — Too little socialization and too little individualization creates isolation.

- Quadrant B — Too little socialization and too high individualization creates rebellion.

- Quadrant C — Too high socialization and too little individualization creates conformity.

- Quadrant D — While the match that organizations want to create is high socialization and high individualization for a creative environment. This is what it takes to survive in a very competitive environment... having people grow with the organization, but doing the right thing when others want to follow the easy path.

This can become quite a balancing act. Individualism favors individual rights, loosely knit social networks, self respect, and personal rewards and careers—it may become look out for Number One! Socialization or collectivism favors the group, harmony, and asks “What is best for the organization?” Organizations need people to challenge, question, and experiment while still maintaining the culture that binds them into a social system.

Organization Development

Organization Development (OD) is the systematic application of behavioral science knowledge at various levels, such as group, inter-group, organization, etc., to bring about planned change (Newstrom, Davis, 1993). Its objectives is a higher quality of work-life, productivity, adaptability, and effectiveness. It accomplishes this by changing attitudes, behaviors, values, strategies, procedures, and structures so that the organization can adapt to competitive actions, technological advances, and the fast pace of change within the environment.

There are seven characteristics of OD (Newstrom, Davis, 1993):

- Humanistic Values: Positive beliefs about the potential of employees (McGregor's Theory Y).

- Systems Orientation: All parts of the organization, to include structure, technology, and people, must work together.

- Experiential Learning: The learners' experiences in the training environment should be the kind of human problems they encounter at work. The training should NOT be all theory and lecture.

- Problem Solving: Problems are identified, data is gathered, corrective action is taken, progress is assessed, and adjustments in the problem solving process are made as needed. This process is known as Action Research.

- Contingency Orientation: Actions are selected and adapted to fit the need.

- Change Agent: Stimulate, facilitate, and coordinate change.

- Levels of Interventions: Problems can occur at one or more level in the organization so the strategy will require one or more interventions.

Quality of Work Life

Quality of Work Life (QWL) is the favorableness or unfavorableness of the job environment (Newstrom, Davis, 1993). Its purpose is to develop jobs and working conditions that are excellent for both the employees and the organization. One of the ways of accomplishing QWL is through job design. Some of the options available for improving job design are:

- Leave the job as is but employ only people who like the rigid environment or routine work. Some people do enjoy the security and task support of these kinds of jobs.

- Leave the job as is, but pay the employees more.

- Mechanize and automate the routine jobs.

- And the area that OD loves—redesign the job.

When redesigning jobs there are two spectrums to follow—job enlargement and job enrichment. Job enlargement adds a more variety of tasks and duties to the job so that it is not as monotonous. This takes in the breadth of the job. That is, the number of different tasks that an employee performs. This can also be accomplished by job rotation.

Job enrichment, on the other hand, adds additional motivators. It adds depth to the job—more control, responsibility, and discretion to how the job is performed. This gives higher order needs to the employee, as opposed to job enlargement which simply gives more variety. The chart below illustrates the differences (Cunningham & Eberle, 1990):

The benefits of enriching jobs include:

- Growth of the individual

- Individuals have better job satisfaction

- Self-actualization of the individual

- Better employee performance for the organization

- Organization gets intrinsically motivated employees

- Less absenteeism, turnover, and grievances for the organization

- Full use of human resources for society

- Society gains more effective organizations

There are a variety of methods for improving job enrichment (Hackman and Oldham, 1975):

- Skill Variety: Perform different tasks that require different skill. This differs from job enlargement which might require the employee to perform more tasks, but require the same set of skills.

- Task Identity: Create or perform a complete piece of work. This gives a sense of completion and responsibility for the product.

- Task Significant: This is the amount of impact that the work has on other people as the employee perceives.

- Autonomy: This gives employees discretion and control over job related decisions.

- Feedback: Information that tells workers how well they are performing. It can come directly from the job (task feedback) or verbally form someone else.

For a survey activity, see Hackman & Oldham's Five Dimensions of Motivating Potential.

Action Learning

An unheralded British academic was invited to try out his theories in Belgium—it led to an upturn in the Belgian economy. “Unless your ideas are ridiculed by experts they are worth nothing,” says the British academic Reg Revans, creator of action learning.

Action Learning can be viewed as a formula: [L = P + Q]:

- Learning (L) occurs through a combination of

- programmed knowledge (P) and

- the ability to ask insightful questions (Q).

Action learning has been widely used in Europe for combining formal management training with learning from experience. A typical program is conducted over a period of 6 to 9 months. Teams of learners with diverse backgrounds conduct field projects on complex organizational problems that require the use of skills learned in formal training sessions. The learning teams then meet periodically with a skilled instructor to discuss, analyze, and learn from their experiences.

Revans basis his learning method on a theory called System Beta, in that the learning process should closely approximate the scientific method. The model is cyclical—you proceed through the steps and when you reach the last step you relate the analysis to the original hypothesis and if need be, start the process again. The six steps are:

- Formulate Hypothesis (an idea or concept)

- Design Experiment (consider ways of testing truth or validity of idea or concept)

- Apply in Practice (put into effect, test of validity or truth)

- Observe Results (collect and process data on outcomes of test)

- Analyze Results (make sense of data)

- Compare Analysis (relate analysis to original hypothesis)

Note that you do not always have to enter this process at step 1, but you do have to complete the process.

Revans suggest that all human learning at the individual level occurs through this process. Note that it covers what Jim Stewart (1991) calls the levels of existence:

- We think — cognitive domain

- We feel — affective domain

- We do — action domain

All three levels are interconnected, i.e., what we think influences us and is influenced by what we do and feel.

Change

In its simplest form, discontinuity in the work place is change. - Knoster & Villa, 2000

Our prefrontal cortex is a fast and agile computational device that is able to hold multiple threads of logic at once so that we can perform fast calculations. However, it has its limits with working memory in that it can only hold a handful of concepts at once, similar to the RAM in a PC. In addition, it burns lots of high energy glucose (blood sugar), which is expensive for the body to produce. Thus when given lots of information, such as when a change is required, it has a tendency to overload and being directly linked to the amygdala (the emotional center of the brain) that controls our fight-or-flight response, it can cause severe physical and psychological discomfort. (Koch, 2006)

Our prefrontal cortex is marvelous for insight when not overloaded. But for normal everyday use, our brain prefers to run off its hard-drive—the basal ganglia, which has a much larger storage area and stores memories and our habits. In addition, it sips rather than gulps food (glucose).

When we do something familiar and predictable, our brain is mainly using the basal ganglia, which is quite comforting to us. When we use our prefrontal cortex, then we are looking for fight, flight, or insight. Too much change produces fight or flight syndromes. As change agents we want to produce insight into our learners so that they are able to apply their knowledge and skills not just in the classroom, but also on the job.

And the way to help people come to insight is to allow them to come to their own resolution. These moments of insight or resolutions are called epiphanies—sudden intuitive leap of understanding that are quite pleasurable to us and act as rewards. Thus you have to resist the urge to fill in the entire picture of change, rather you have to leave enough gaps so that the learners are allowed to make connections of their own. Doing too much for the learners can be just as bad, if not worse, than not doing enough.

Doing all the thinking for learners takes their brains out of action, which means they will not invest the energy to make new connections.

ntations

Presentations and reports are ways of communicating ideas and information to a group. But unlike a report, a presentation carries the speaker's personality better and allows immediate interaction between all the participants.

A report is the orderly presentation of the results of the research which seeks truth and interprets facts into constructive ideas and suggestions (Gwinn, 2007). A report is normally built on research that finds, develops, or substantiates knowledge. Once all the facts are collected, they are then organized and presented in a report designed to meet a need for specific information.

A presentation is created in the same manner as a report; however, it adds one additional element — The Human Element.

A good presentation contains at least four elements:

- Content — It contains information that people need. But unlike reports, which are read at the reader's own pace, presentations must account for how much information the audience can absorb in one sitting.

- Structure — It has a logical beginning, middle, and end. It must be sequenced and paced so that the audience can understand it. Where as reports have appendices and footnotes to guide the reader, the speaker must be careful not to loose the audience when wandering from the main point of the presentation.

- Packaging — It must be well prepared. A report can be reread and portions skipped over, but with a presentation, the audience is at the mercy of a presenter.

- Human Element — A good presentation will be remembered much more than a good report because it has a person attached to it. However, you must still analyze the audience's needs to determine if they would be better met if a report was sent instead

eadership and Visioning

Visions are the first step in the goal setting and planning process. While mission statements guide the organization in its day-to-day operations, visions provide a sense of direction in the long term — they provide the means to the future.Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus (2007) conclude, “Leaders articulate and define what has previously remained implicit or unsaid; then they invent images, metaphors, and models that provide a focus for new attention. By so doing, they consolidate or challenge prevailing wisdom. In short, an essential factor in leadership is the capacity to influence and organize meaning for the members of the organization.”They continue, “Managers are people who do things right and leaders are people who do the right thing. The difference may be summarized as activities of vision and judgment — effectiveness verses activities of mastering routine — efficiency.”Bennis and Nanus describe leaders as “creating dangerously” — they change the basic metabolism of the organization. Tom Peters (1988) wrote that leaders, “must create new worlds. And then destroy them; and then create anew.” What is interesting, is that Peters defines visions as aesthetic and moral — as well as strategically sound. Which would sort of knock Hitler's quest of the world as being a vision. Visions that are merely proclaimed, but not lived convincingly are nothing more than mockeries of the process.Many visions almost sound like value statements. And its no wonder why since they come from within us. One that follows this path is Johnson & Johnson's vision; they call it their Credo.This credo saved J&J during their Tylenol crisis as it give them specific guidelines to follow. Thus, visions can be about change and/or they can be about the way an organization wants to live or operate. Tom Peters further wrote about visions, “They are personal — and group centered. Developing a vision and values is a messy, artistic process. Living it convincingly is a passionate one, beyond any doubt.” J&J is quite passionate about living theirs.Peters goes further into his explanation of visions by writing:- Effective visions are inspiring. . .

- Effective visions are clear and challenging. . .

- Effective visions make sense in the market place, and, by stressing flexibility and execution, stand the test of time in a turbulent world. . .

Bennis is thinking along the same lines as Peters in that the way he describes visions as being “creating dangerously” is not that some madman, such as Hitler, may use them, but rather because visions “create anew.” There is an old saying of be careful of what you wish for. For example, Starbucks' vision was a plan for growth — and even though it did grow, this growth has brought different problems along with it. So when achieving visions, you have to be prepared to go through “dangerous” times.Creating Visions

The U.S. Army's (1987) vision is the first step in goal setting:- Visions: what will the organization look like in the future?

- Goals: create the framework.

- Objectives: create measurable terms.

- Tasks: how will the objectives be accomplished?

- Timelines: when will they be accomplished?

- Follow-up during the actual performance to ensure all the above is being met.

Visions are quite often the simple part, with the hard part being the execution — turning the vision into reality. For example, Kennedy's vision of putting a man on the moon was the simple part. The hard part was the actual accomplishment of the vision.The important part is not really the framework or method used to create a vision, but rather the path one must take after the vision is created. For example, Iacocca's vision pulled Chrysler away from their deathbed, not because Iacocca created the vision, but because they then had the guts to walk that vision. Steve Job's vision of Apple being the epicenter of the technology industry has held true since they sold their first computer. However, once IBM entered the PC scene (and this was only after they saw what Apple was doing), it was not long before Apple became a distant player. Apple should have died a couple of times since then. Yet, no one technology company has had as many innovations as Apple has and they are still creating them. . . it is why they still survive in a very competitive environment.Strategy and Tactics

Strategies are forward-looking. They provide the guidelines for growth, thus they are often closely related with visions. Tactical is more or less “present” orientated and is more or less related to mission statements. For more information, seeStrategy & Tactics..Where there is no vision, the people perish. — Proverbs 29:18

The Voice

The voice is probably the most valuable tool of the presenter. It carries most of the content that the audience takes away. One of the oddities of speech is that we can easily tell others what is wrong with their voice, e.g. too fast, too high, too soft, etc., but we have trouble listening to and changing our own voices.

There are five main terms used for defining vocal qualities (Grant-Williams, 2002):

- Volume: How loud the sound is. The goal is to be heard without shouting. Good speakers lower their voice to draw the audience in, and raise it to make a point.

- Tone: The characteristics of a sound. An airplane has a different sound than leaves being rustled by the wind. A voice that carries fear can frighten the audience, while a voice that carries laughter can get the audience to smile.

- Pitch: How high or low a note is. Pee Wee Herman has a high voice, Barbara Walters has a moderate voice, while James Earl Jones has a low voice.

- Pace: This is how long a sound lasts. Talking too fast causes the words and syllables to be short, while talking slowly lengthens them. Varying the pace helps to maintain the audience's interest.

- Color: Both projection and tone variance can be practiced by taking the line “This new policy is going to be exciting” and saying it first with surprise, then with irony, then with grief, and finally with anger. The key is to over-act. Remember Shakespeare's words “All the world's a stage” — presentations are the opening night on Broadway!

There are two good methods for improving your voice:

1. Listen to it! Practice listening to your voice while at home, driving, walking, etc. Then when you are at work or with company, monitor your voice to see if you are using it how you want to.

2. To really listen to your voice, cup your right hand around your right ear and gently pull the ear forward. Next, cup your left hand around your mouth and direct the sound straight into your ear. This helps you to really hear your voice as others hear it... and it might be completely different from the voice you thought it was! Now practice moderating your voice.

The Body

Your body communicates different impressions to the audience. People not only listen to you, they also watch you. Slouching tells them you are indifferent or you do not care... even though you might care a great deal! On the other hand, displaying good posture tells your audience that you know what you are doing and you care deeply about it. Also, a good posture helps you to speak more clearly and effective.

Your body communicates different impressions to the audience. People not only listen to you, they also watch you. Slouching tells them you are indifferent or you do not care... even though you might care a great deal! On the other hand, displaying good posture tells your audience that you know what you are doing and you care deeply about it. Also, a good posture helps you to speak more clearly and effective.Throughout you presentation, display (Smith, Bace, 2002).:

- Eye contact: This helps to regulate the flow of communication. It signals interest in others and increases the speaker's credibility. Speakers who make eye contact open the flow of communication and convey interest, concern, warmth, and credibility.

- Facial Expressions: Smiling is a powerful cue that transmits happiness, friendliness, warmth, and liking. So, if you smile frequently you will be perceived as more likable, friendly, warm, and approachable. Smiling is often contagious and others will react favorably. They will be more comfortable around you and will want to listen to you more.

- Gestures: If you fail to gesture while speaking, you may be perceived as boring and stiff. A lively speaking style captures attention, makes the material more interesting, and facilitates understanding.

- Posture and body orientation: You communicate numerous messages by the way you talk and move. Standing erect and leaning forward communicates that you are approachable, receptive, and friendly. Interpersonal closeness results when you and your audience face each other. Speaking with your back turned or looking at the floor or ceiling should be avoided as it communicates disinterest.

- Proximity: Cultural norms dictate a comfortable distance for interaction with others. You should look for signals of discomfort caused by invading other's space. Some of these are: rocking, leg swinging, tapping, and gaze aversion. Typically, in large rooms, space invasion is not a problem. In most instances there is too much distance. To counteract this, move around the room to increase interaction with your audience. Increasing the proximity enables you to make better eye contact and increases the opportunities for others to speak.

- Voice. One of the major criticisms of speakers is that they speak in a monotone voice. Listeners perceive this type of speaker as boring and dull. People report that they learn less and lose interest more quickly when listening to those who have not learned to modulate their voices.

Active Listening

Good speakers not only inform their audience, they also listen to them. By listening, you know if they are understanding the information and if the information is important to them. Active listening is NOT the same as hearing! Hearing is the first part and consists of the perception of sound.

Listening, the second part, involves an attachment of meaning to the aural symbols that are perceived. Passive listening occurs when the receiver has little motivation to listen carefully. Active listening with a purpose is used to gain information, to determine how another person feels, and to understand others. Some good traits of effective listeners are:

Listening, the second part, involves an attachment of meaning to the aural symbols that are perceived. Passive listening occurs when the receiver has little motivation to listen carefully. Active listening with a purpose is used to gain information, to determine how another person feels, and to understand others. Some good traits of effective listeners are:- Spend more time listening than talking (but of course, as a presenter, you will be doing most of the talking).

- Do not finish the sentence of others.

- Do not answer questions with questions.

- Aware of biases. We all have them. We need to control them.

- Never daydream or become preoccupied with their own thoughts when others talk.

- Let the other speaker talk. Do not dominate the conversation.

- Plan responses after others have finished speaking...NOT while they are speaking. Their full concentration is on what others are saying, not on what they are going to respond with.

- Provide feedback but do not interrupt incessantly.

- Analyze by looking at all the relevant factors and asking open-ended questions. Walk the person through analysis (summarize).

- Keep the conversation on what the speaker says...NOT on what interest them.

Listening can be one of our most powerful communication tools! Be sure to use it!

Part of the listening process is getting feedback by changing and altering the message so the intention of the original communicator is understood by the second communicator. This is done by paraphrasing the words of the sender and restating the sender's feelings or ideas in your own words, rather than repeating their words. Your words should be saying, “This is what I understand your feelings to be, am I correct?” It not only includes verbal responses, but also nonverbal ones. Nodding your head or squeezing their hand to show agreement, dipping your eyebrows to show you don't quite understand the meaning of their last phrase, or sucking air in deeply and blowing out hard shows that you are also exasperated with the situation.

Carl Rogers (1957) listed five main categories of feedback (Demos, Zuwaylif, 1962). They are listed in the order in which they occur most frequently in daily conversations (notice that we make judgments more often than we try to understand):

- Evaluative: Makes a judgment about the worth, goodness, or appropriateness of the other person's statement.

- Interpretive: Paraphrasing to explain what another person's statement mean.

- Supportive: Attempt to assist or bolster the other communicator

- Probing: Attempt to gain additional information, continue the discussion, or clarify a point.

- Understanding: Attempt to discover completely what the other communicator means by her statements.

Nerves

The main enemy of a presenter is tension, which ruins the voice, posture, and spontaneity. The voice becomes higher as the throat tenses. Shoulders tighten up and limits flexibility while the legs start to shake and causes unsteadiness. The presentation becomes canned as the speaker locks in on the notes and starts to read directly from them.

First, do not fight nerves, welcome them!Then you can get on with the presentation instead of focusing in on being nervous. Actors recognize the value of nerves...they add to the value of the performance. This is because adrenaline starts to kick in. It's a left over from our ancestors' “fight or flight” syndrome. If you welcome nerves, then the presentation becomes a challenge and you become better. If you let your nerves take over, then you go into the flight mode by withdrawing from the audience. Again, welcome your nerves, recognize them, let them help you gain that needed edge! Do not go into the flight mode! When you feel tension or anxiety, remember that everyone gets them, but the winners use them to their advantage, while the losers get overwhelmed by them.

Tension can be reduced by performing some relaxation exercises. Listed below are a couple to get you started:

- Before the presentation: Lie on the floor. Your back should be flat on the floor. Pull your feet towards you so that your knees are up in the air. Relax. Close your eyes. Feel your back spreading out and supporting your weight. Feel your neck lengthening. Work your way through your body, relaxing one section at a time — your toes, feet, legs, torso, etc. When finished, stand up slowly and try to maintain the relaxed feeling in a standing position.

- If you cannot lie down: Stand with you feet about 6 inches apart, arms hanging by your sides, and fingers unclenched. Gently shake each part of your body, starting with your hands, then arms, shoulders, torso, and legs. Concentrate on shaking out the tension. Then slowly rotate your shoulders forwards and the backwards. Move on to your head. Rotate it slowly clockwise, and then counter-clockwise.

- Mental Visualization: Before the presentation, visualize the room, audience, and you giving the presentation. Mentally go over what you are going to do from the moment you start to the end of the presentation.

- During the presentation: Take a moment to yourself by getting a drink of water, take a deep breath, concentrate on relaxing the most tense part of your body, and then return to the presentation saying to your self, “I can do it!”

- You do NOT need to get rid of anxiety and tension! Channel the energy into concentration and expressiveness.

- Know that anxiety and tension is not as noticeable to the audience as it is to you.

- Know that even the best presenters make mistakes. The key is to continue on after the mistake. If you pick up and continue, so will the audience. Winners continue! Losers stop!

- Never drink alcohol to reduce tension! It affects not only your coordination but also your awareness of coordination. You might not realize it, but your audience will!

Questioning

Keep cool if a questioner disagrees with you. You are a professional! No matter how hard you try, not everyone in the world will agree with you!

Although some people get a perverse pleasure from putting others on the spot, and some try to look good in front of the boss, most people ask questions from a genuine interest. Questions do not mean you did not explain the topic good enough, but that their interest is deeper than the average audience.

Always allow time at the end of the presentation for questions. After inviting questions, do not rush ahead if no one asks a question. Pause for about 6 seconds to allow the audience to gather their thoughts. When a question is asked, repeat the question to ensure that everyone heard it (and that you heard it correctly). When answering, direct your remarks to the entire audience. That way, you keep everyone focused, not just the questioner. To reinforce your presentation, try to relate the question back to the main points.

Always allow time at the end of the presentation for questions. After inviting questions, do not rush ahead if no one asks a question. Pause for about 6 seconds to allow the audience to gather their thoughts. When a question is asked, repeat the question to ensure that everyone heard it (and that you heard it correctly). When answering, direct your remarks to the entire audience. That way, you keep everyone focused, not just the questioner. To reinforce your presentation, try to relate the question back to the main points.Make sure you listen to the question being asked. If you do not understand it, ask them to clarify. Pause to think about the question as the answer you give may be correct, but ignore the main issue. If you do not know the answer, be honest, do not waffle. Tell them you will get back to them... and make sure you do!

Answers that last 10 to 40 seconds work best. If they are too short, they seem abrupt; while longer answers appear too elaborate. Also, be sure to keep on track. Do not let off-the-wall questions sidetrack you into areas that are not relevant to the presentation.

If someone takes issue with something you said, try to find a way to agree with part of their argument. For example, “Yes, I understand your position...” or “I'm glad you raised that point, but...” The idea is to praise their point and agree with them as audiences sometimes tend to think of “us verses you.” You do not want to risk alienating them.

Preparing the Presentation

After a concert, a fan rushed up to famed violinist Fritz Kreisler and gushed, “I'd give up my whole life to play as beautifully as you do.” Kreisler replied, “I did.”

To fail to prepare is to prepare to fail

The first step of a great presentations is preplanning. Preparing for a presentation basically follows the same guidelines as a meeting (a helpful guide on preparing and conducting a meeting, such as acquiring a room, informing participants, etc.)

The second step is to prepare the presentation. A good presentation starts out with introductions and may include an icebreaker such as a story, interesting statement or fact, or an activity to get the group warmed up. The introduction also needs an objective, that is, the purpose or goal of the presentation. This not only tells you what you will talk about, but it also informs the audience of the purpose of the presentation.

The second step is to prepare the presentation. A good presentation starts out with introductions and may include an icebreaker such as a story, interesting statement or fact, or an activity to get the group warmed up. The introduction also needs an objective, that is, the purpose or goal of the presentation. This not only tells you what you will talk about, but it also informs the audience of the purpose of the presentation.Next, comes the body of the presentation. Do NOT write it out word for word. All you want is an outline. By jotting down the main points on a set of index cards, you not only have your outline, but also a memory jogger for the actual presentation. To prepare the presentation, ask yourself the following:

- What is the purpose of the presentation?

- Who will be attending?

- What does the audience already know about the subject?

- What is the audience's attitude towards me (e.g. hostile, friendly)?

A 45 minutes talk should have no more than about seven main points. This may not seem like very many, but if you are to leave the audience with a clear picture of what you have said, you cannot expect them to remember much more than that. There are several options for structuring the presentation:

- Timeline: Arranged in sequential order.

- Climax: The main points are delivered in order of increasing importance.

- Problem/Solution: A problem is presented, a solution is suggested, and benefits are then given.

- Classification: The important items are the major points.

- Simple to complex: Ideas are listed from the simplest to the most complex. Can also be done in reverse order.

You want to include some visual information that will help the audience understand your presentation. Develop charts, graphs, slides, handouts, etc.

After the body, comes the closing. This is where you ask for questions, provide a wrap-up (summary), and thank the participants for attending.

Notice that you told them what they are about to hear (the objective), told them (the body), and told them what they heard (the wrap up).

And finally, the important part — practice, practice, practice. The main purpose of creating an outline is to develop a coherent plan of what you want to talk about. You should know your presentation so well, that during the actual presentation, you should only have to briefly glance at your notes to ensure you are staying on track. This will also help you with your nerves by giving you the confidence that you can do it. Your practice session should include a live session by practicing in front of coworkers, family, or friends. They can be valuable at providing feedback and it gives you a chance to practice controlling your nerves. Another great feedback technique is to make a video or audio tape of your presentation and review it critically with a colleague.

Habits

We all have a few habits, and some are more annoying than others. For example, if we say “uh”, “you know,” or put our hands in our pockets and jingle our keys too often during a presentation, it distracts from the message we are trying to get across.

The best way to break one of these distracting habits is with immediate feedback. This can be done with a small group of coworkers, family, or friends. Take turns giving small off-the-cuff talks about your favorite hobby, work project, first work assignment, etc. The talk should last about five minutes. During a speaker's first talk, the audience should listen and watch for annoying habits.

After the presentation, the audience should agree on the worst two or three habits that take the most away from the presentation. After agreement, each audience member should write these habits on a 8 1/2 "x 11" sheet of paper (such as the word “Uh”). Use a magic marker and write in BIG letters.

The next time the person gives her or his talk, each audience member should wave the corresponding sign in the air whenever they hear or see the annoying habit. For most people, this method will break a habit by practicing at least once a day for one to two weeks.

Slides

Your slides should not only be engaging, but also easy to understand quickly (Reynolds, 2008). Think “Visual” — such as pictures, charts, and drawings that support what you will be speaking about. You want the slides to support and clarify the story you will be telling rather than simply be redundant text that mimics what you are saying.

Paint a Picture to Tell a Story

Making bad slides is easy... and all too common, thus you need to invest in not only your slides, but also in your visual presentation (Duarte, 2008).

Resources for making better slide show presentations:

Tips and Techniques For Great Presentations

Eleanor Roosevelt was a shy young girl who was terrified at the thought of speaking in public. But with each passing year, she grew in confidence and self-esteem. She once said, “No one can make you feel inferior, unless you agree with it.”- If you have handouts, do not read straight from them. The audience does not know if they should read along with you or listen to you read.

- Do not put both hands in your pockets for long periods of time. This tends to make you look unprofessional. It is OK to put one hand in a pocket but ensure there is no loose change or keys to jingle around. This will distract the listeners.

- Do not wave a pointer around in the air like a wild knight branding a sword to slay a dragon. Use the pointer for what it is intended and then put it down, otherwise the audience will become fixated upon your “sword”, instead upon you.

- Do not lean on the podium for long periods. The audience will begin to wonder when you are going to fall over.

- Speak to the audience...NOT to the visual aids, such as flip charts or overheads. Also, do not stand between the visual aid and the audience.

- Speak clearly and loudly enough for all to hear. Do not speak in a monotone voice. Use inflection to emphasize your main points.

- The disadvantages of presentations is that people cannot see the punctuation and this can lead to misunderstandings. An effective way of overcoming this problem is to pause at the time when there would normally be punctuation marks.

- Learn the name of each participant as quickly as possible. Based upon the atmosphere you want to create, call them by their first names or by using Mr., Mrs., Miss, Ms.

- Tell them what name and title you prefer to be called.

- Listen intently to comments and opinions. By using a lateral thinking technique (adding to ideas rather than dismissing them), the audience will feel that their ideas, comments, and opinions are worthwhile.

- Circulate around the room as you speak. This movement creates a physical closeness to the audience.

- List and discuss your objectives at the beginning of the presentation. Let the audience know how your presentation fits in with their goals. Discuss some of the fears and apprehensions that both you and the audience might have. Tell them what they should expect of you and how you will contribute to their goals.

- Vary your techniques (lecture, discussion, debate, films, slides, reading, etc.)

- Get to the presentation before your audience arrives; be the last one to leave.

- Be prepared to use an alternate approach if the one you've chosen seems to bog down. You should be confident enough with your own material so that the audience's interests and concerns, not the presentation outline, determines the format. Use your background, experience, and knowledge to interrelate your subject matter.

- When writing on flip charts use no more than 7 lines of text per page and no more than 7 word per line (the 7 x 7 rule). Also, use bright and bold colors, and pictures as well as text.

- Consider the time of day and how long you have got for your talk. Time of day can affect the audience. After lunch is known as the graveyard section in training and speaking circles as audiences will feel more like a nap than attending a presentation.

- Most people find that if they practice in their head, the actual talk will take about 25 percent longer. Using a flip chart or other visual aids also adds to the time. Remember — it is better to finish slightly early than to overrun.

Leadership: Strategy & Tactics

Strategy is the creation of a unique and valuable market position supported by a system of activities that fit together in a complementary way (Porter, 1980). It is about making choices, trade-offs, and deliberately choosing to be different.It should not be confused with operational effectiveness or best practices — what is good for everybody and what every business should be doing, e.g., performing the same activities your competitors perform, TQM, benchmarking, or being a learning organization (Porter, 1980). Thus, when developing strategies, the goal is to be different from your competitors. However, this does not mean that you are willing to do anything, but rather determine where the opportunities lie that you can best exploit.All strategic plans need to tie in with the organization's strategic plan. That is, in going back to the definition of strategy, the leaders of the organization should create the unique and valuable market position; while your goal is to support the organization with activities that fit together in a complementary way. Now that does not mean you cannot do things differently or set your own goals. It simply means that you need to keep your leaders visions and goals in focus when setting your goals. For example, if the leaders have ethics and diversity at the forefront of their strategic vision, you cannot put elearning and knowledge management at the forefront of your strategic goals. However, that does not mean you cannot use elearning and knowledge management technologies to bring about ethical and diversity goals.Visioning

Visioning is the start of any strategic plan. Once your leaders have set the organizational strategic plans, you need to determine how best your department can bring about changes that will support those plans. And while their strategic plan needs to be unique, you need to think along the same lines.Visioning strategy is best performed using a four-prong approach:- Internal Audit — Where are you now (snapshot)?

- Reading and Research — Where can you grow?

- Organization Vision — Where is the organization going?

- Vision — Where do you want to grow?

Note that first three steps can be performed in just about any order; however, the last step will normally be last in the process as it is based upon the other three prongs.Tactical

Strategies are forward-looking. They provide the guidelines for growth. With strategies, you are in reality, speaking of future performance gaps and how you are going to overcome them.Tactical is more or less present or now-orientated. It is about present performance gaps and how you are going to overcome them in order to support the strategies.What have you done today to enhance (or at least insure against the decline of) the relative overall useful skill level of your work force vis-à-vis competitors — Tom Peters inThriving on ChaosWhen Peters writes of “enhancing,” he is speaking of the strategic plans that will grow the employees to meet tomorrow's challenges. When he writes of “insure against the decline of,” he is speaking of the tactical impediments that are presently challenging employees from meeting expected performance standards. In order to grow, you must be able to ward off present roadblocks. Thus, tactical plans are about providing performance stability so that change may take affect for growth.Strategies normally look an average of about five years into the future (with a range of about one to ten years). Tactics look ahead just far enough to secure objectives set by strategy. Thus, tactics are characterized by adroitness, ingenuity, or skill. Note that tactics is from the Greek taktika — matters pertaining to arrangement. On the other hand, strategy has its roots in “office of a General” or “to lead”).Command & Control

Command & Control does not mean micro-management (observing and controlling work to such a degree that you stifle creativity and teamwork); but rather building the bare necessities that allows the organization to achieve its goals, while at the same time preserving and building networks that brings out the best in its people, such as drive and innovation.There are four basic functions used within organizations to achieve their visions and goals: Command, Control, Leadership, and Management:1. Command — forming and imparting visions:- Well formed visions

- Clear goals and objectives for achieving the visions

- QUALITY, low volume communications throughout the organization

- Involvement to ensure results

2. Leadership — achieving visions through people:- Standard Bearer

- Developing

- Integrating

3. Management — implementing processes for achieving the visions:- Planning

- Organizing

- Budgeting

4. Control — ensuring resources went where they were supposed to go:- Routine, high volume communications

- Coordination between activities

- Structure to reduce uncertainty

With Control and Management the ultimate goal is efficiency — addressing how well the process was accomplished (form); while with Command and Leadership the ultimate goal is effectiveness— achieving goals and mission (results). Generally, to achieve “form,” one must conceptualize “processes”; while to achieve “results,” one must conceptualize “tasks.”Thus, command and leadership decide what the organization should be doing, while control and management ensure that the resources used to achieve the results are used efficiently (without waste).Frameworks of Command & Control

Command and Leadership use the following framework:- Creating — creating a vision or task to achieve results

- Planning — how you will achieve the result

- Implementing — putting the plan into action

- Follow-up — ensuring that it gets done

Related to the Command & Control framework is OODA.Control and Management uses the following framework:- Observe — see what has happened

- Compare — what actually happened to what was supposed to happen

- Decide — does the comparison show that the objectives were met and determine what needs changing?

- Follow-up — ensure the change actually ha

Leadership: Strategy & Tactics

Strategy is the creation of a unique and valuable market position supported by a system of activities that fit together in a complementary way (Porter, 1980). It is about making choices, trade-offs, and deliberately choosing to be different.It should not be confused with operational effectiveness or best practices — what is good for everybody and what every business should be doing, e.g., performing the same activities your competitors perform, TQM, benchmarking, or being a learning organization (Porter, 1980). Thus, when developing strategies, the goal is to be different from your competitors. However, this does not mean that you are willing to do anything, but rather determine where the opportunities lie that you can best exploit.All strategic plans need to tie in with the organization's strategic plan. That is, in going back to the definition of strategy, the leaders of the organization should create the unique and valuable market position; while your goal is to support the organization with activities that fit together in a complementary way. Now that does not mean you cannot do things differently or set your own goals. It simply means that you need to keep your leaders visions and goals in focus when setting your goals. For example, if the leaders have ethics and diversity at the forefront of their strategic vision, you cannot put elearning and knowledge management at the forefront of your strategic goals. However, that does not mean you cannot use elearning and knowledge management technologies to bring about ethical and diversity goals.Visioning

Visioning is the start of any strategic plan. Once your leaders have set the organizational strategic plans, you need to determine how best your department can bring about changes that will support those plans. And while their strategic plan needs to be unique, you need to think along the same lines.Visioning strategy is best performed using a four-prong approach:- Internal Audit — Where are you now (snapshot)?

- Reading and Research — Where can you grow?

- Organization Vision — Where is the organization going?

- Vision — Where do you want to grow?

Note that first three steps can be performed in just about any order; however, the last step will normally be last in the process as it is based upon the other three prongs.Tactical

Strategies are forward-looking. They provide the guidelines for growth. With strategies, you are in reality, speaking of future performance gaps and how you are going to overcome them.Tactical is more or less present or now-orientated. It is about present performance gaps and how you are going to overcome them in order to support the strategies.What have you done today to enhance (or at least insure against the decline of) the relative overall useful skill level of your work force vis-à-vis competitors — Tom Peters inThriving on ChaosWhen Peters writes of “enhancing,” he is speaking of the strategic plans that will grow the employees to meet tomorrow's challenges. When he writes of “insure against the decline of,” he is speaking of the tactical impediments that are presently challenging employees from meeting expected performance standards. In order to grow, you must be able to ward off present roadblocks. Thus, tactical plans are about providing performance stability so that change may take affect for growth.Strategies normally look an average of about five years into the future (with a range of about one to ten years). Tactics look ahead just far enough to secure objectives set by strategy. Thus, tactics are characterized by adroitness, ingenuity, or skill. Note that tactics is from the Greek taktika — matters pertaining to arrangement. On the other hand, strategy has its roots in “office of a General” or “to lead”).Command & Control

Command & Control does not mean micro-management (observing and controlling work to such a degree that you stifle creativity and teamwork); but rather building the bare necessities that allows the organization to achieve its goals, while at the same time preserving and building networks that brings out the best in its people, such as drive and innovation.There are four basic functions used within organizations to achieve their visions and goals: Command, Control, Leadership, and Management:1. Command — forming and imparting visions:- Well formed visions

- Clear goals and objectives for achieving the visions

- QUALITY, low volume communications throughout the organization

- Involvement to ensure results

2. Leadership — achieving visions through people:- Standard Bearer

- Developing

- Integrating

3. Management — implementing processes for achieving the visions:- Planning

- Organizing

- Budgeting

4. Control — ensuring resources went where they were supposed to go:- Routine, high volume communications

- Coordination between activities

- Structure to reduce uncertainty

With Control and Management the ultimate goal is efficiency — addressing how well the process was accomplished (form); while with Command and Leadership the ultimate goal is effectiveness— achieving goals and mission (results). Generally, to achieve “form,” one must conceptualize “processes”; while to achieve “results,” one must conceptualize “tasks.”Thus, command and leadership decide what the organization should be doing, while control and management ensure that the resources used to achieve the results are used efficiently (without waste).Frameworks of Command & Control

Command and Leadership use the following framework:- Creating — creating a vision or task to achieve results

- Planning — how you will achieve the result

- Implementing — putting the plan into action

- Follow-up — ensuring that it gets done

Related to the Command & Control framework is OODA.Control and Management uses the following framework:- Observe — see what has happened

- Compare — what actually happened to what was supposed to happen

- Decide — does the comparison show that the objectives were met and determine what needs changing?

- Follow-up — ensure the change actually ha

No comments:

Post a Comment