OODA Loop

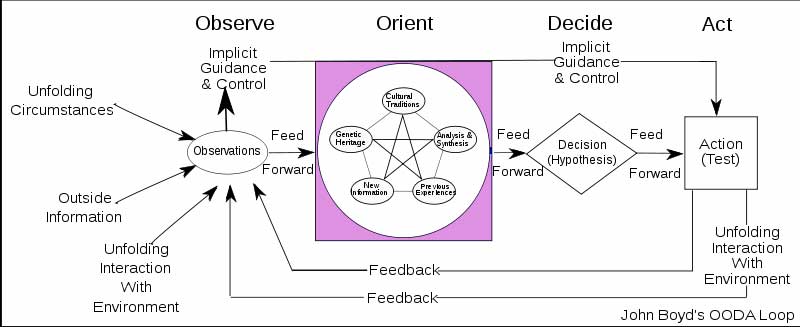

The OODA Loop model was developed by Col. John Boyd, USAF (Ret) during the Korean War. It is a concept consisting of the following four actions:

- Observe

- Orient

- Decide

- Act

This looping concept referred to the ability possessed by fighter pilots that allowed them to succeed in combat. It is now used by the U.S. Marines and other organizations. The premise of the model is that decision-making is the result of rational behavior in which problems are viewed as a cycle of Observation, Orientation (situational awareness), Decision Making, and Action. Boyd diagramed the OODA loop as shown in the figure below:

Cycling Through OODA

An entity (whether an individual or an organization) that can process this cycle more quickly than an opponent can “get inside” the opponent's decision cycle and gain the advantage.

Observation

Scan the environment and gather information from it.

Orientation

Use the information to form a mental image of the circumstances. That is, synthesize the data into information. As more information is received, you "deconstruct" old images and then "create" new images. Note that different people require different levels of details to perceive an event. Often, we imply that the reason people cannot make good decisions, is that people are bad decisions makers — sort of like saying that the reason some people cannot drive is that they are bad drivers. However, the real reason most people make bad decisions is that they often fail to place the information that we do have into its proper context. This is where "Orientation" comes in. Orientation emphasizes the context in which events occur, so that we may facilitate our decisions and actions. That it, orientation helps to turn information into knowledge. And knowledge, not information, is the real predictor of making good decisions.

Decision

Consider options and select a subsequent course of action.

Action

Carry out the conceived decision. Once the result of the action is observed, you start over. Note that in combat (or competing against the competition), you want to cycle through the four steps faster and better than the enemy, hence, it is a loop.

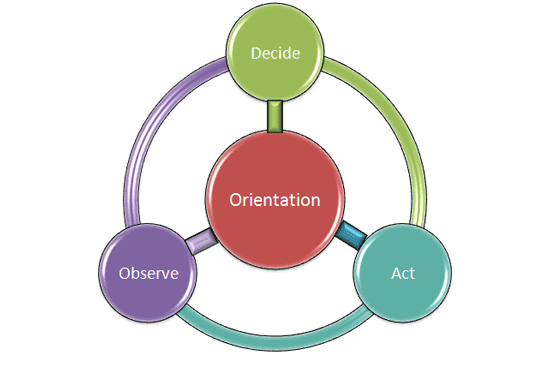

Interactive Web

The loop doesn't mean that individuals or organizations have to observe, orient, decide, and act, in the order as shown in the diagram above. Rather, picture the loop as an interactive web with orientation at the core, as shown in the diagram below. Orientation is how we interpret a situation, based on culture, experience, new information, analysis, synthesis, and heritage

Thus, the loop is actually a set of interacting loops that are kept in continuous operation.

SOAP

Another variation of the OODA cycle is SOAP that is used by paramedic's and medical techs. SOAP is a standard process for: Situation, Observation, Analysis, Perform.

Leadership: Organization Ethos vs. Warrior Ethos

While the U.S. Army's Warrior Ethos may look entirely unrelated to civilian organizations, the concepts behind it are perhaps an idea role-model for all organizations.

Warrior Ethos

The Warrior Ethos are four principles of conduct extracted from the Soldier's Creed:

I will always place the mission first.

I will never accept defeat.

I will never quit.

I will never leave a fallen comrade.

While we normally picture a warrior as someone engaged or experienced in warfare, the U.S. Army pictures it more as someone who is engaged aggressively or energetically in an activity, cause, or conflict. Thus it becomes the foundation of soldiers in both peacetime and periods of conflict.

Ethos is the spirit (esprit d' corps), moral nature, or guiding beliefs of a community or individual.

I will always place the mission first

Missions are basically an organization's means of living out its visions. For example, in 1982, Johnson & Johnson was confronted with a crisis when seven people died after ingesting Tylenol capsules laced with cyanide. News traveled quickly and caused a nationwide panic.

I don't think they can ever sell another product under that name. There may be an advertising person who thinks he can solve this and if they find him, I want to hire him, because then I want him to turn our water cooler into a wine cooler. — Advertising genius, Jerry Della Femina as told to the New York Times right after the crises.

However, Johnson & Johnson won the public's heart and trust with its commitment to protecting its customers during the Tylenol poisoning crises. They dealt with the crises by living their corporate business philosophy — Our Credo (similar to an ethos in that it defines one's system of values and beliefs). It was crafted in the 1940's by Robert Wood Johnson who believed that businesses have responsibilities to society. The credo stressed that it was important for them to be responsible in working for the public interest.

Thus, they approached the crises by living their Credo. From the start of the crises they:

- informed the public and medical community

- established relations with the Chicago Police, FBI, and the Food and Drug Administration

- stopped production of Tylenol

- recalled all Tylenol capsules from the market

- immediately put up a reward of $100,000 for the killer

In turn, the media did much of the company's work by praising Johnson & Johnson's socially responsible actions. Johnson & Johnson's top management put customer safety first, NOT their company's profit or other financial concerns. In other words, they did the right thing. At first, it is easy to believe that such a move was against the best interest of the company's stockholders, but when you put customers and employees first, it actually benefits the stockholders in the long run.

Johnson & Johnson has effectively demonstrated how a major business ought to handle a disaster. This is no Three Mile Island accident in which the company's response did more damage than the original incident. What Johnson & Johnson executives have done is communicate the message that the company is candid, contrite, and compassionate, committed to solving the murders and protecting the public. — Jerry Knight, The Washington Post on October 11, 1982.

Once the crises ended, they started actions to put their organization back on track:

- New Tylenol capsules were introduced in November with triple-seal tamper resistant packaging

- Provided $2.50 coupons that were good towards the purchase of any Tylenol product

- Over 2,250 sales people made presentations to people in the medical community

Johnson & Johnson could have disclaimed any possible link between Tylenol and the seven sudden deaths. In other similar cases, companies put themselves first and ended up doing more damage to their reputations than if they had immediately taken responsibility for the crisis. For example, traces of benzene were found in Source Perrier's bottled water. Rather than holding themselves accountable for the incident, they claimed that the contamination resulted from an isolated incident and recalled a limited number of Perrier bottles in North America. When benzene was found in Perrier bottled water in Europe, an embarrassed Source Perrier had to announce a worldwide recall on the bottled water and were immediately criticized for having little integrity and for disregarding public safety.

Lesson learned: Discover your vision, set your mission, and then live by it

I will never accept defeat and I will never quit

While the U.S. Army separates these two principles, for the purpose of this discussion, I will put them together since they are interrelated.

Going back to Johnson & Johnson, their executives wept not only out of grief, but some out of guilt. One top executive said, “it was like lending someone your car and seeing them killed in a traffic accident.” During the crises they performed a nation-wide recall of 31 million bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol capsules. Many of their advisors told them that this was unnecessary as the tainted capsules had only been found in the Chicago area, thus it would be a waste of money.

Yet, not wanting to see even one more tragedy occur, the top executives stuck to their Credo. After seeing the media and public's positive reaction, opposition within the company all but vanished.

In January 1993, tragedy struck when the deadly E.coli virus was traced to Jack in the Box's Pacific Northwest restaurants. The 300 food poisoning cases were linked to undercooked beef in the hamburger chain. Jack in the Box initially did not handle the public relations crisis very well as it took two days before they removed all meat from its restaurants. Jack in the Box officials did not take immediate decisive action to shut down all the stores for a few days and teach employees how to properly grill hamburgers.

However, not too long after the incident, the company developed the most comprehensive and multi-dimensional food safety system in the fast-food industry. Called HACCP (hazard analysis critical control points), the program consisted of “farm to fork” procedures that included microbial meat testing by Jack in the Box suppliers and in-restaurant grilling procedures to ensure fully cooked hamburgers. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has since called the program the industry model.

Once you are sure that a decision is morally correct, you stand by it. This does not mean you stand by mistakes. For example, after Jack in the Box's saw that their wait-and-see attitude was taking extreme criticism by the media and public, they backed away from it and learned by it — this lesson helped them to become not only a stronger player in the fast food industry but also a leader in food safety.

Compare Johnson & Johnson, Jack in the Box, and Perrier's responses to crises:

- Prepared to act responsibly in a crises due to a deeply held belief

- Learns from their mistake

- A fiasco occurs because they did not want to hold themselves accountable

Lessons learned:

When you are sure that your decision is morally correct, stand by it

Do not only learn from your mistakes, but also grow yourself from them

I will never leave a fallen comrade

While this principle was aimed at the battlefield, the philosophy behind of it reaches far into the boardrooms of corporations.

One of the favorite tactics of organizations to increase their value, especially in lean times, is to downsize. Organizations are famous for proclaiming that their workers are their most important asset, yet during a financial crises they turn 180 degrees and not only let their most valued assets fall, but also cause them to fall in the first place.

In a speech to the Academy of Management in 1996, Donald Hastings, CEO of Lincoln Electric, called downsizing and rightsizing “dumbsizing.” Note that Lincoln Electric is one of the leaders in its field and has not laid off since its inception in 1948. The company has been through all the hard times like everyone else, yet it chooses to redeploy people rather than lay them off, such as having factory workers selling products in the field. Another company, the Saturn Division of General Motors, did similar redeployments in the 1990s. Why?

Because innovations, productivity improvements, and other such measures are not likely to be sustained over time when workers fear that they will work themselves out of a job (Locke, 1995). Using the analogy of pruning, it is generally done to create new growth or to get rid of diseased parts. Yet, when organizations prune, they have no desire to create new growth (or they would train and redeploy) and they normally miss the diseased portions because the ones who got them into trouble in the first place (the executives and managers) are still there!

The evidence indicates that downsizing is guaranteed to accomplish only one thing — it makes organizations smaller. — Jeffery Pfeffer (1998).

In fact, the consequences of downsizing are:

- stock prices that lag 5 to 45% behind the competition (in more than 1/2 the cases they lagged 17% to 48%)

- it does not necessarily increase productivity or profits

- downsizing tends to be repetitive (2/3 of organizations repeat it soon after)

- it does not fix or improve core processes

- it can be readily copied so it offers no competitive advantage

- it has unanticipated costs that limit its benefits

With all the negative connotations associated with downsizing, very few firms use other means to avoid downsizing (1994 American Management Association survey), such as:

- reducing work hours

- reducing pay

- taking outsourced work back

- building inventories

- freeze hiring and reshuffle workers

- do training, maintenance, etc.

- refrain from hiring during peak demands

- encourage people to innovate (product, services, & markets)

- transfer people to sales to build demand

One of the fads in management is forced ranking — managers reflect on how each team member is performing, relative to others, and are then ranked in order from the highest to the lowest performers. The ideal is to identify top-performers and weed out the bottom-ones. For example, the top 20 percent might be amply rewarded, while the bottom 10 percent are shown the door.

It creates a zero-sum game, and so it tends to discourage cooperation. — Steve Kerr, a managing director at Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

Contrast the above with U.S. Marine Drill Sergeants, who are considered some of the toughest warriors on earth. Yet they hold one deeply held value on the human spirit — they will never give up on any recruits who do not give up on themselves (Katzenbach & Santamaria 1999). Their value-driven philosophy allows them to train some of the most effective warriors on the battlefield.

While Marine Drill Sergeants never give up on those who do not give up on themselves, forced ranking schemes often pits employees against each other, rather than fostering a climate of a collaborative work environment, which often leads to dysfunctional and hyper-competitive workplace. Thus these employees who have not given up on themselves may be shown the door, indeed, they might even be better performers than some of their competitors.

Lessons learned:

You must truly value your most important asset

Never quit on those who do not to quit on themselves

orizontal Leadership: Bridging the Information Gap

Bridge Over the Euphrates River

Technology Review published a story, How Technology Failed in Iraq, about one of the largest resistance efforts, code-named Objective Peach (pdf), of Saddam's Army during the early-morning hours of April 3, 2003, near a key bridge on the Euphrates River, located about 30 kilometers southwest of Baghdad in the Karbala Gap. The battle turned out to be a fairly conventional fight between tanks and other armored vehicles. During this operation, a four lane fixed bridge was secured and a second bridge was put in place byEngineer units.

The Iraqi attack was quite large, thus it should have been known well in advance since the U.S. troops were supported by a large technology assisted intelligence network, such as aircraft spotters, satellite-mounted motion sensors, heat detectors, image sensors, and communications eavesdroppers. Commanders had high-bandwidth links to tap into this intelligence network while in the field.

Yet, during Objective Peach, Lt. Col. a battalion commander with the 69th Armor of the Third Infantry Division, was starved for information about Iraqi troop movements and as he said in the Technology Review article, “I would argue that I was the intelligence-gathering device for my higher headquarters.”

Yet, during Objective Peach, Lt. Col. a battalion commander with the 69th Armor of the Third Infantry Division, was starved for information about Iraqi troop movements and as he said in the Technology Review article, “I would argue that I was the intelligence-gathering device for my higher headquarters.”As night fell, Marcone realized the situation was getting quite threatening so he arrayed his battalion in a defensive position on the far side of the bridge. It was not long before his fighting force of 1,000 soldiers, 30 tanks, and 14 Bradley fighting vehicles was facing three brigades of Iraq fighters composed of about 30 tanks, 70 armored personnel carriers, artillery, and about 7,000 Iraqi soldiers coming at him from three different directions.

This Iraqi deployment should have been fairly easy to detect, yet they received no information until the Iraqis slammed into them. This was not an isolated case as one key node was consistently falling off the intelligence network — the front-line troops. This soon became known as the digital divide: at the division level and above, the view of the battle space was adequate, yet among the front-line troops, such as Marcone's, the situational awareness was terrible.

Yet, a new U.S. intelligence paradigm was employed at the time — force transformation, which was to use a number of technologies so that field commanders, such Marcone, would be networked into an information gathering and disseminating array. This information was to help units project not only power, but also act as protection. Lucky for Marcone, the tactical adroitness of his warriors easily overcame the attacking Iraqi army. Thus they won on superior tactical strength, rather than a vision of total knowledge.

One of the breakdowns in this intelligence network were the antenna relays carried by the advancing units. These antennas needed to be stationary to function and be within a line of sight to pass information to each other. However, these units were moving much too fast and too far for the system to work. In a few cases, they were attacked while they stopped to set up their antenna relays.

A second breakdown happened in the rear units — their connectivity was too good. They received so much data from some of their sensors that they couldn't process it all; thus they had to stop accepting some of their information feeds.

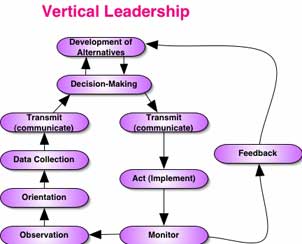

Horizontal Verses Vertical

One of the arguments for this intelligence breakdown is that it is doctrinal in nature, rather than technological — the communication breakdown was out of date as it used vertical command and control rather than a horizontal flow. Information was to go up the chain of command, so that the major commanders in the rear could interpret it, and then send down their decisions. This resulted in major time delays. Thus the information was out there, yet it was not getting to the people who needed it the most.

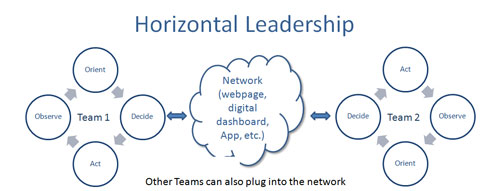

In contrast, during the 2001 war in Afghanistan, special-operations forces were organized into small teams (about two dozen soldiers) who patrolled the mountains near the Pakistan border on horseback. Their mission was to root out the Taliban and al-Qaeda forces. Rather that being linked to a central command, the teams were networked to each other — no one person was in tactical command.

Each team also had a key node — the alpha geek, whose job was to manage the flow of information between his team and the others. Thus, rather than being confined to the “corporate IT department,” the information geeks were actually in the field.

These special force units also maintained a web page, that arranged all the data collected by the teams into information that could easily be accessed by all.

Horizontal Leadership

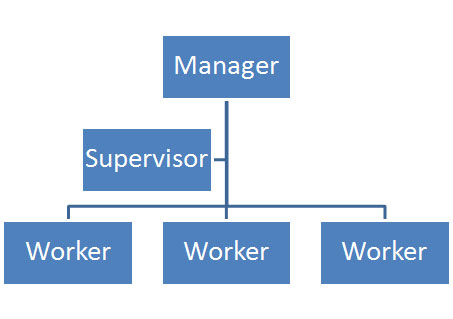

Vertical leadership refers to an individual who is in a formal position of power, such as being the hierarchical head of a division. But if we start looking at leadership as being a total system, rather than an individual, then information becomes networked, rather than running up the ladder, and then back down.

From this point-of-view, the various work teams receive leadership contributions from every member, not just the official designated leader. Now this does not mean that everyone is a boss or manager, for there are those who main purpose is to set the vision for the various teams. However, once the vision is received, it becomes the job of everyone to see to it that the vision is actually implemented.

Thus, we still have a Howard Schultz who visions an experience, rather than just a cup of coffee; and a Steve Jobs, who visions a digital lifestyle, rather than just a computer.

But rather than a vertical stream of information that goes vertically between Jobs or Schultz and their employees, their employees are now beside them on the same horizontal information stream.

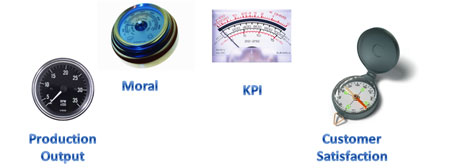

Digital Dashboards

A digital dashboard is an interface, resembling an automobile's dashboard, that organizes and presents information in a way that is easy to read. One of their uses is to present Key Performance Indicators (KPI) in a visual and easy to understand manner. Yet a lot of the literature coming out is directing them towards executives (see Executive Dashboards and KPI).

While some key information should only go to select individuals, organizations need to start thinking more along the lines of the special-operations forces operating in Afghanistan — pulling information from all sources and then providing the means, in this case via the internet, so that all teams have access to it.

One of the advantages of horizontal leadership is that it fits in more with theOODA Loop model that was developed by Col. John Boyd, USAF (Ret). When Colonel John Boyd first introduced the OODA: Observe-Orient-Decide-Act). Thus, it allows for faster decision making:

versus

Horizontal leadership is a means of involving networked teams to ensure a leader's vision is executed.

Thus, rather than visualizing the organization as a traditional organization chart:

...it needs to be pictured more as a network:

orizontal Leadership Instrument

This survey will help to assess your team's Horizontal Leadership Capabilitiesby identifying areas that it performs well in and areas that need improvement.

Instructions

Each member of the team needs to take the survey.

This survey contains statements about interactions within your organization. Next to each statement, circle the number that represents how strongly you feel about the statement by using the following scoring system:

- Almost Always True — 5

- Frequently True — 4

- Occasionally True — 3

- Seldom True — 2

- Almost Never True — 1

Be honest about your choices as there are no right or wrong answers — it is only for your team's self-assessment.

| 1 | Most of the information and instructions that I require to perform my work comes from my coworkers, rather than my supervisors and managers. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | The reports and information I create goes to my peers or immediate working group, rather than upwards to my superiors. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | If needed, I could perform the duties and tasks of my coworkers if they became unavailable. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | I consider the people I work with to be a "High Performance Team," rather than a work group. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | I feel that I'm am connected to others within and outside my organization to the correct degree so that they understand my problems and needs. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | I know where I stand with my leaders and how satisfied they are with my work. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | I have such a high degree of confidence with the people I work with that I would defend their decisions they made if they were not present to do so. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 8 | I rarely feel that I am left out of the "information loop." | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 9 | We are flexible enough to rapidly adjust to changing situations. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 10 | I have extremely effective relationships with the people I work with. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Total your score: __________.

Assessing Your team's Horizontal Capability

The highest score possible is 50, while the lowest score possible is a 10. A completely horizontal team would score a 50, while a totally vertical (hierarchical) team would score a 10. While almost no team will score a perfect 50, the goal should be to come as close to it as possible.

Once all the team members have completed the survey, compile the scores for each question. With the help of your team, choose one to four areas to improve, depending on the degree of perceived difficulty. This improvement phase should normally last about two to three months. Once the time period is over, the team should retake the survey, and repeat the improvement process until they have have reached a level that they are satisfied with. The survey can then be used to check the team's Horizontal Leadership performance capability to ensure it is maintaining its prescribed level.

No comments:

Post a Comment